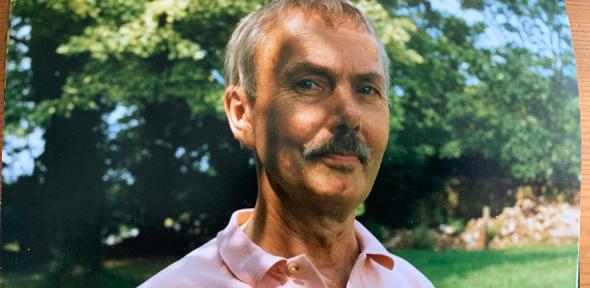

Stuart Warren

Philip Evans

I was an undergraduate at Churchill from 1967 to 1970. Stuart’s impact on the undergraduate chemists of the late ‘60s was extraordinary : he was both the lightning and the thunder that followed!

Context is needed : 1967, when I came up, was the start of an extraordinary time in higher education : Bob Dylan’s songs, the war in Vietnam, the Paris students of May ’68 are but symptoms of a heady time of a societal re-alignment nationally and a sort of democratisation in education. There was Woodstock and free love….

Well, no, not really.In the late ‘60s many of us were, boringly, worried about examination results and whether the SRC grants we wanted for Ph.Ds etc. would be forthcoming.

In 1967, the science/maths lectures were almost uniformly bad: the maths dept, who gave the courses for scientists, were the worst; but the chemistry dept were only marginally better.By early ’68, some enterprising Nat Sci students(no Natskis yet)had organised a questionnaire re lecturing; there was a staff/student committee set up via real elections.I was one of these student revolutionaries elected – a more unlikely one you could never find.

And that is when Stuart arrived. It would have been ’68 or more probably ’69. Not only were his lectures meticulously prepared with clear handouts, he was also a lecturer of real gifts : always a clarity and empathy with us in front of him, trying our best, being but two aspects. He was more than a breath of fresh air – within a few lectures he had established « how it could and should be done ». In that sense he was indeed a revolutionary and, like the best of that ilk, changed the future course of Cambridge chemistry teaching forever.

He also organised group tutorials.As I recall these were in his office, with discussions, debates, questions ; and all this with coffee, cakes and biscuits. In my mind’s eye the coffee was brewed in a fume cupboard in the corner of the office. Surely not ? The mind is playing tricks perhaps, but I like my mental picture. Colourful cravats, treating us as the intelligent adults that we were, a seriousness of purpose, lightly displayed. It was an introduction of how to be a serious scientist – a lesson many of us never forgot.

We of the "class of ‘67" etc. owe him a great deal. I was greatly saddened to learn of his death, as all the above makes clear.

One further personal thought if I may: I would also like to name Dudley Williams (organic chemist, Churchill) and Alan Sharpe (inorganic chemist, Jesus) who also took pains in their teaching and who were important to me in my growth both as a chemist and as a person. But it was half a century ago; they’re all gone now.

David Howells

In response to Philip Evans' recollections listed above and in Chem@Cam 61 (Dec 2020) David wrote:

I was saddened to see the references to Stuart Warren’s death but reading Phillip Evan’s memories nevertheless brought back a smile as I recall working in his small research group at that time (1970 - 1973).

Philip’s recollections were correct; Stuart’s first lecture course to undergraduates was to second year students in 1968/69 and his approach to teaching was such a breath of fresh air that I was very happy to accept the chance to subsequently work in his group and for 2 years I was actually the entire group! His approach to teaching was based on just a few teaching principles which subsequently have become accepted as best practice. Firstly he worked on the basis that it was not possible for students having up to 3 lectures in a morning to concentrate intensely for 60 unremitting minutes and so he would turn up 2 or 3 minutes late, would finish 2 or 3 minutes early and would have a couple of minutes break in the middle to amuse us with an anecdote. Secondly he appreciated that lectures were meant for passing information to students rather than them being a test of how a student could listen and write quickly and accurately at the same time. To ensure that concepts were absorbed in the lectures themselves and with students listening and focussing, he had prepared an A4 booklet which essentially contained the lecture notes. This seems so obvious now but at that time it was quite exceptional.

His analytical approach to all aspects of his life extended also to his practice as a Research Supervisor. Rather than coming round to my bench in Lab 287 “to not help me twice a day”, he stressed throughout that it was my PhD and our contact was usually restricted to lunch on Fridays - indeed with coffee brewed in the fume cupboard. As we munched through sandwiches - his invariably beef with horseradish from the Panton Arms - we would laugh about his passion for off spin bowling, the Goons, his occasionally-irreverent impersonations of the more senior members of the teaching fraternity, and life and everything. And then as lunch was finishing he would ask what I had been doing that week and we would then discuss where it was leading and he would make suggestions of possible avenues that I may care to explore. it was never dictatorial, he was always there to help if I asked for assistance and his man-management skills made me feel that I was part of a partnership even though,in truth, he was at the helm.

They were really fun times in a colourful era in a colourful Department which had some lively young individuals - Stuart, Tony Kirby, Ian Fleming, Dudley Williams and others. I shall never forget those times, especially the humour, and will be eternally grateful for Stuart’s analytical brilliance as a thinker, communicator and educator and how his example influenced my subsequent career. He was an exceptional person.

David Morris

In the hustle and bustle of everyday life I had only just heard that Dr Stuart Warren passed away earlier in the year.

I studied natural sciences at Churchill College (graduating 1978) and subsequently gained a PhD under the direction of Dr Dudley Williams (1981). As an undergraduate I found Stuart’s lectures inspirational. I can remember arriving at the Lensfield Road lecture theatre on a Saturday morning with hands so cold from the cycle ride in that I could barely grip my pen – it didn’t matter. Stuart’s lectures were superbly organised and hugely informative as he developed his theme and revealed to us the secrets of organic chemistry. Stuart took you from where your knowledge base stood and by the end of the lecture you had a clear sense of advancement not to say a sense of being royally entertained.

As a Churchill College tutor he was uniquely gifted. Alert and responsive to an individual’s needs he encouraged us to ask questions and then challenged us with his own questions. Supervisions were also focused on the learner’s agenda and he had the ability to see with great clarity the perspective of his tutees. Stuart was such a great teacher.

I have taught chemistry and medicine in a variety of situations and have always tried to engage the teaching principles and approach that Stuart so clearly demonstrated.

Alan Davidson

I would like to contribute my own comments as I was one of Stuart’s early PhD students (1973-76). I was greatly influenced by him and very grateful for all his help.

I was extremely fortunate to be taught by Stuart as an undergraduate and also to have him as my PhD supervisor. All supervisions were challenging, slightly nerve racking, but actually quite enjoyable. The same could be said for the research group meetings; I am not sure my teeth have ever fully recovered from the Godfrey’s lemon buns. Not only did I learn a great deal of organic chemistry from Stuart but I also learnt how to run a research group - to get the best out of a PhD student and for the student to get the best out of a Ph.D. I hope some of my PhD students benefited from this training!